5 Aprile 2021

Confessioni di un bevitore nascosto di Lambrusco (rivisitato)

Nel 1987, ho scritto un articolo sul Lambrusco per la rivista americana Quarterly Review of Wines. A quel tempo il Lambrusco era il vino importato più venduto negli Stati Uniti, anche se era noto come “Coca-Cola italiana” perché era frizzante e dolce e adorato dai bevitori indiscriminati di vino americani perché era “nice on ice“.

Nel corso della sua lunga storia, il Lambrusco ha conquistato la nomea come uno dei vini italiani più vivaci e conviviali, ma anche come uno dei più incompresi e sottovalutati e, in definitiva, uno dei più amati. Apprezzato soprattutto dalla gente della sua terra emiliana, ma anche da un crescente numero di forestieri che non devono fare chissà quale sforzo per amarlo vista la sua dote innata di attirare con il fragore delle bollicine per poi lasciarti – o almeno a me – sedotto senza speranza.

I miei primi elogi al Lambrusco mi hanno reso una specie di cane sciolto tra gli scrittori di vino, sia italiani che stranieri. Ma col tempo il Lambrusco è cresciuto in statura, guadagnandosi il rispetto degli esperti e un nuovo apprezzamento tra i consumatori italiani ed esteri.

Quando ho scritto quell’articolo più di trent’anni fa, ho confessato di aver superato i miei dubbi sul Lambrusco e di non sentirmi più obbligato a berlo di nascosto.

…[gli] Emiliani, molti dei quali lo bevono quotidianamente e più di qualcuno si guadagna da vivere con esso, si irritano quando sentono denigrare il Lambrusco.

“Ignoranza, ecco cos’è”, scattò Nando Cavalli al mio suggerimento che il vino non è esattamente venerato dagli intenditori all’estero. “La gente pensa che siccome è così facile da bere non può essere preso sul serio. Ma quello che ignorano è che il Lambrusco è uno dei vini più sani e gratificanti del mondo, un grande vino in una classe a sé.”

Il Cavaliere Ferdinando Cavalli, nominato dalla Repubblica italiana per i suoi successi di imprenditore vitivinicolo, probabilmente conosceva le sottigliezze del Lambrusco come nessun’altro in Emilia. Era metà mattina di una bella giornata primaverile quando Cavalli stappò una bottiglia di quello che lui chiamava Fior Fiore, assicurandomi, mentre la vivace schiuma rosa si placava nel mio bicchiere, che mi avrebbe fatto più bene di una spremuta d’arancia. “Tre per cento di alcol”, esclamò. “Potresti berne un’intera bottiglia e non sentire nulla”.

Una fragranza che mi ricordava i fiori di ciliegio salì alle mie narici prima ancora che avessi sollevato il bicchiere. I degustatori di vino coscienziosi sorseggiano ma non deglutiscono a quell’ora, ma con il nettare di Nando non c’era bisogno di sputare. Dal rigoglioso aroma fruttato, con un leggero pizzicore a rinfrescare il palato, era delizioso come una ciotola di fragole appena raccolte.

Cavalli, con un sorriso trionfale, tracannò il suo bicchiere e riempì nuovamente i calici, perorando al tempo stesso le virtù del Lambrusco. “È assolutamente naturale”, inneggiò. “Non è trattato con niente. No, no, nemmeno l’anidride solforosa. Ora, di quanti vini si può dire questo?”.

– “Il vero Lambrusco è sempre stato fermentato in bottiglia, non in vasche pressurizzate”, disse Cavalli. “La maggior parte dei vini di oggi non sono fatti per durare. Ma quando tutto è a posto, cioè assolutamente puro, il Lambrusco può durare a lungo”.

– “Quanto a lungo?” Chiesi.

– “Hah!” rispose lui, felice che avessi colto lo spunto. “Vieni con me”.

Impugnando una torcia elettrica, Cavalli scese lesto una precipitosa rampa di scale di pietra fino alla sua cantina appena illuminata, con me che brancolavo dietro di lui in una stanza cavernosa con il soffitto a volta e il pavimento in terra battuta dove si trovavano delle casse di legno da cui sporgevano i fondi di bottiglie champagnotte capovolte.

Sollevò cautamente una bottiglia e la mise controluce, scrutandola attraverso la polvere e lo spessore del vetro verde smeraldo. “Sembra a posto”, disse, “ma prenderò anche un’altra per essere sicuro. Dopotutto è un sessantuno.”

“Sessantuno?” Dissi io. “Lambrusco?”

“Certo”, esultò il Cavaliere. “Purtroppo il cinquantotto è finito”.

Tornati al piano di sopra, mise le bottiglie in posizione verticale per far depositare la feccia e per ingannare l’attesa aprì un Lambrusco secco dell’ultima annata. Inutile dire che anche questo non andava sputato. “Bevilo”, comandò. “Il vero Lambrusco è un elisir che ti lascia sempre in forma e sorridente”.

Quando la feccia si fu depositata in modo soddisfacente, Cavalli afferrò il collo di una bottiglia del ’61 e, puntandola a distanza sopra un lavandino, tolse la gabbietta e diede al sughero avvizzito un cauto giro. Quanto è bastato per far scaturire un’esplosione e schizzare di viola la parete di piastrelle bianche, suscitando un grido di gioia da parte del padrone di casa.

Gli ci vollero tre giri ripetuti a breve distanza per riempiere a metà il mio bicchiere di schiuma che andava trasformandosi in uno stupefacente liquido violaceo. Ho sollevato il bicchiere e cominciato a girarlo con delicatezza, lasciando che si formassero degli archetti che sembravano finestre gotiche color malva. Al naso, suggeriva marmellata d’uva, terra umida, pomodori secchi e qualcosa di speziato, come la noce moscata. Vivace al palato come un vino giovane, il suo sapore era secco ma morbido con note di prugne mature e catrame. E lì, sul finale, c’era quel suggerimento di amaro corroborante che caratterizza il Lambrusco di qualsiasi età, anche di ventisei anni.

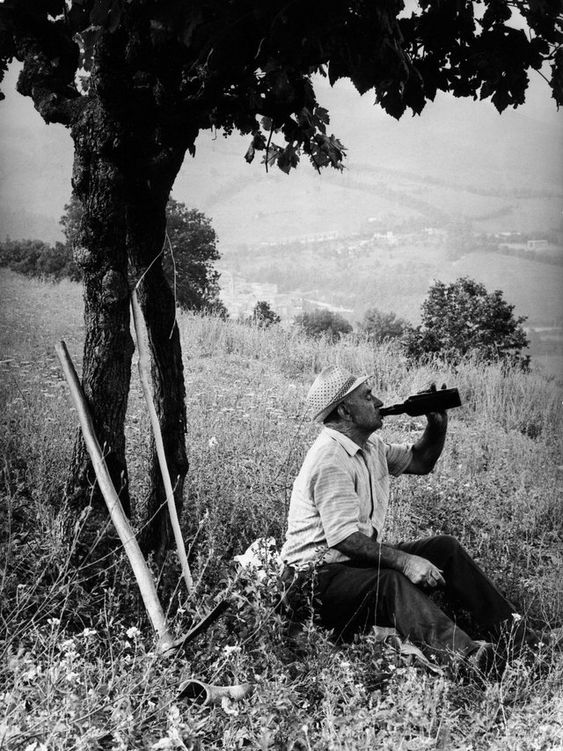

Era appena passato mezzogiorno quando finimmo la degustazione, prudentemente senza lasciare una goccia. Cavalli raccolse altre bottiglie di varie annate e le depositò sul mio grembo mentre salivamo sulla sua Alfa Romeo e ci dirigevamo verso un ristorante perso nelle pianure emiliane. Mentre sfrecciavamo attraverso corridoi di viti ad alto fusto, mi sentivo in forma e sorridente, proprio come aveva decretato Nando. E proprio in quel momento feci un voto silenzioso di non sorseggiare mai più il Lambrusco di nascosto.

ENGLISH

Confessions of a Closet Lambrusco Drinker (Revisited)

In 1987, I wrote an article about Lambrusco for the American magazine Quarterly Review of Wines. At that time Lambrusco was the best-selling imported wine in the U.S.A., though it had become known as “Italian Coca-Cola” because it was bubbly and sweet and adored by America’s indiscriminate wine drinkers because it was “nice on ice.”

Lambrusco over its long history has endured as one of the most vivacious and convivial of Italian wines, but also one of the most misunderstood and mistreated, and, ultimately, one of its most beloved. Beloved above all by the people of its Emilian homeland but also by a growing number of outsiders who didn’t really need to learn to love it because it’s a wine that has a way of beckoning you with a burst of bubbles one day and leaving you—or at least me—hopelessly seduced.

My early praise of Lambrusco made me something of a maverick among writers on wine, whether Italian or foreign. But over time Lambrusco has grown in stature, earning respect among experts and new appreciation among consumers in Italy and abroad.

When I wrote that article I confessed to overcoming my doubts about Lambrusco and no longer feeling that I had to drink it on the sly, as what I described as a “closet Lambrusco drinker.” My conversion was heavily influenced by a meeting in 1987 described in the following excerpt:

“….Emilians, many of whom drink it daily and more than a few of whom make a living from it, bristle when they hear Lambrusco maligned.

“Ignorance, that’s what it is,” snapped Nando Cavalli at my suggestion that the wine is not exactly revered by connoisseurs abroad. “People think that because it’s so easy to drink they can’t take it seriously. But what they ignore is that Lambrusco is one of the most wholesome and rewarding wines in the world, a great wine in a class by itself.”

Cavaliere Ferdinando Cavalli, knighted by the Italian government for his achievements as a winemaker, probably knows the ins and outs of Lambrusco as well as any man in Emilia. It was mid-morning on a fine spring day when Cavalli popped the cork on a bottle of what he called Fior Fiore, assuring me, as the vivid pink foam subsided in my glass, that it would do me more good than fresh orange juice. “Three percent alcohol,” he exclaimed. “You could drink a whole bottle and not feel a thing.”

A fragrance that reminded me of cherry blossoms wafted up to my nostrils before I had even lifted the glass. Conscientious wine tasters swish but don’t swallow at that hour, but with Nando’s nectar there was no need to spit. Vitally fruity, with a palate-cleansing prickle, it was as luscious as a bowl of fresh strawberries.

Cavalli, beaming triumphantly, downed his glass and poured us both another, all the time feistily building the case for the virtues of Lambrusco. “It’s absolutely natural,” he chirped. “Not treated with anything. No, no, not even sulfur dioxide. Now, how many wines can you say that about?”

“The real Lambrusco was always fermented in bottles, not pressurized tanks,” said Cavalli. “Most wines these days aren’t made to last. But when everything is right, so that it’s absolutely pure, Lambrusco can last a long time.”

“How long?” I asked.

“Hah!” he replied, delighted that I’d taken the cue. “Come with me.”

Wielding a flashlight, Cavalli spryly descended a precipitous flight of stone stairs to his dim cantina with me groping behind him into a cavernous room with vaulted ceiling and packed earth floor upon which were several wooden crates with the butts of inverted Champagne-type bottles protruding from them.

He lifted a bottle cautiously and held it up to the light, peering through the dust on the thick, emerald green glass. “Looks fine,” he said, “but I’ll bring another just to be sure. It’s a sixty-one, after all.”

“Sixty-one?” I said. “Lambrusco?”

“Of course,” said Cavalli cavalierly. “Unfortunately, the fifty-eight is finished.”

Back upstairs, he placed the bottles upright to let the dregs settle as we sampled a dry Lambrusco from the latest vintage. There was to be no spitting of that, either. “Drink up,” he commanded. “Genuine Lambrusco is an elixir that leaves you feeling fit and smiling.”

When the dregs had settled to his satisfaction, Cavalli grasped the neck of a bottle of the ’61 and, aiming it away from himself over a sink, removed the wire stay and gave the wizened cork a gingerly twist. It needed no more coaxing, exiting in an explosion that splattered purple over the white tile wall and elicited a shout of glee from my host.

It took him three short, foamy pours to fill my glass half way with the astonishingly bright violet liquid. I lifted the glass and gave the wine a gentle swish, which left arches on the side of the glass like mauve-tinted gothic windows. To the nose, it suggested grape jam, damp earth, sun-dried tomatoes and something spicy, like nutmeg. As lively on the palate as a young wine, its flavor was dry but mellow with hints of ripe plums and tar. And there at the finish was that suggestion of bracing bitter that characterizes Lambrusco of any age, even twenty-six years.

It was just past noon when we finished tasting, prudently not leaving a drop. Cavalli gathered more bottles from various vintages and deposited them on my lap as we got into his Alfa Romeo and headed for a restaurant across the Emilian plains. As we sped through corridors of high-trellised vines, I was feeling fit and smiling, just as Nando had decreed. And right then and there I made a silent vow to never again sip Lambrusco in the closet.